|

«I became a composer because I couldn’t think of anything else to do» We would like to start this interview firstly saying this is an honor for us to be here with you and to interview you about your legendary career, and we would like to begin remembering your early beginnings as a film composer, and asking if you could share with us which was your defining instant, when you felt you were in the right path to become a film composer, in the seventies.

Which were your instincts at first, to become a film composer or a contemporary music composer? Just a composer. Actually I became a composer because I couldn’t think of anything else to do, and I study music, my family was very musical, and I thought if I stayed in college long enough I’d find something I really liked to do, but I graduated as a composer, so I was a composer, so…, and it turned out okay, so I kept doing that. Please, talk to us about your non-film music works, like your compositions “Mixed Elements”, “Excursions”, “And on the Sixth Day”, for oboe and orchestra, “Tyvek Wood”, your piccolo or tuba concerto, or your brass fanfares, outside the film music world.

We are, outside of the film music world, that we love so much, always hoping for more orchestral works by Mr. Broughton. As long as someone ask me for it to play I am happy to write it. Next thing I am going to do is a String Quartet. Those are hard to write, so I am happy to do that too. We enjoyed at Úbeda a few pieces of your concert work, like for instance the piece that you composed for… My son? Yeah, for Oliver. That was beautiful to listen to.

The problem here in Europe maybe, it is that we don’t know about those performances of your work. I am working on it, honestly that’s one thing I am working on, trying to get better distribution and better marketing for that kind of stuff. Maybe in the future a Boxset with all your works together, for all the fans to enjoy?. We can always dream. We will work on it, sure. Focusing in the film music world, which genre would you say you are more comfortable working for, and which is the style you love the most creating music for a film?

Texas Rising? Yeah, Texas Rising. That was a lot more difficult that it had been years before when I was doing westerns, because they are making changes all the time. So first, I thought, and then John and I thought, we have a eight hour movie to do, and that went to ten hours. And they didn’t tell us!. That is two hours more. So we got a lot of music to do, and that is kind of hard. I like animation and theme parks for that, I have one theme park to do in December, which is for a Shanghai park. So I am looking forward to that. About your work with John Debney, for Texas Rising, how was the collaboration?, because it is a co-composition, was there a division of themes?

I did most of the battles, practically all the battles, that’s an agreement that we had. He did most of the Indian stuff. Sometimes if they didn’t like a piece of mine, he would fix it, if they didn’t like a piece of him, I would fix it, we were making changes in each other music depending upon what the producers wanted, I didn’t mind. John is a very good composer, he’s a very nice man, and a good friend, we really had a good time together, it was a hard job, but we really had a good time together.He also has a very good sense of humor, and he keeps very positive when he is doing a work. Focusing, back in the day, in probably, your highlight, the western score for Silverado… Yeah. An score so rousing, sweeping, with full symphonic power and thematic at every turn of the way, how is the story behind the score?, how was your collaboration with the director Lawrence Kasdan?, and how were you attached to the movie at first?

He got other people interviewed, and then he called me and he said: -Ok, I am going to go with you, it is a little bit of a risk, because I have never done any big movies, but I think it is going to work out ok-. And it worked out great!, so… He told me that he wanted “A Traditional Hollywood Western (Score)”, because he was trying to make “A Traditional Hollywood Film”, and he had everything in the movie, everything in the western (genre we have always have) except for the Indians, and I asked about that and he said –It was too expensive- haha. So he literally reconstructed the old fashioned traditional western, because he was trying to make a western for people who had never seen one before, meaning, young people, because, you know, they weren’t making westerns at that time. So he sort of reivented the western and got started up again. And the music became well known inmediately, became a sports theme, so it was on tv all the time…, so yeah, it worked out really well. And you obtained a well deserved nomination to the Academy Awards for Silverado, which are your remembrances of those days, of that moment…? At the Academy Awards? Yes, sharing space with legends like John Barry, Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre… I was sitting next to John Barry’s wife, I had her on my right. Haha. On my left was Maurice Jarre, actually my wife at that time was on my left, then it was Maurice Jarre, and then Georges Delerue, and in front of me there were…, I think, twelve guys, nominated for… The Color Purple, haha. Exactly, and that really made me nuts, haha, because if that’d won all those guys would have won an Oscar. I started to think, I didn’t really expect to win, I surely thought that John Barry might, because he had a pretty score, and it wasn’t usual for a western to win. I think that that year, all of you should have been awarded. Certainly it was a good year. Yeah, that was one of the greatest years for music in the Oscars. Changing the topic to another one of your most beloves works by fans and aficionados around the world, your collaboration with Amblin, Steven Spielberg and the director Barry Levinson, for Young Sherlock Holmes. Could you share with us the story behind the composition of the themes of the score and your collaboration with both of them? Barry and Steven? Yes. Oh, I didn’t meet Steven until we had finished with Young Sherlock Holmes, and he came at the dubbing stage where we were mixing all the music and the dialogue, and he said to Barry: -I really like the score!- Haha Haha, and he kept saying: -I really like the score-. So Barry answered: -Maybe you should meet the composer-, hahahaha Hahahahahaha

Well, that’s pretty common, cause on the piano it is very hard to tell what anything it is going to be. With the orchestra we had a really great time recording it, we had a really great time. Barry were so excited that we were recording in London, he was so excited by the score he gave me an extra week in London all of a sudden, it was really fun.

I agree. So I, you know…, and then later I got more things from Amblin, like Harry and the Hendersons, I did Amazing Stories…, ah, I think the Roger Rabbit things, were Disney or Amblin?, I am not sure Yes, the short films of Roger Rabbit were Amblin, yes. Ok, so I have a long, long run with them.., and also Tiny Toons, it wasn’t Amblin but Steven Spielberg, and he called me after we finished the cartoons, to talk me about the cartoons. He was really the executive producer, because he called a lot. He is some kind of Maestro about the cartoons, and if he didn’t like something, I heard from him soon, but mostly he liked them and he was you know, very complimental. Was it difficult to adapt yourself to the cartooning scoring, like the mickeymousing…?

So it was really interesting, I found a couple of guys, who did it really well, a couple of guys who didn’t do it really well, but…, (for example) John Debney did a couple of them. Oh, I didn’t know that. John and Richard Stone, they’ll have a career after that, doing that stuff, so, it was, it was a lot of fun The CD that was released, the Cartoon Concerto, (I must say) I love that, it is wooonderful.

Stay Tuned?, is it something in the Cartoon Concerto of that film? I am really not sure, I don’t remember, I did not have any input putting that together. Another great one of your scores, Stay Tuned, I love that one, different styles combined together.

The swashbuckling part, the western part… Yeah, we have the cartoons, we have the 1940’s dramas… (will continue)

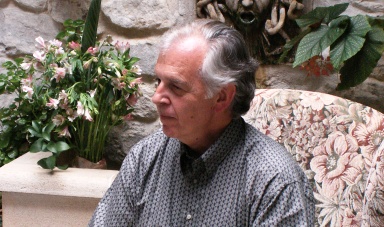

Thanks to Bruce Broughton, Jesús Castro, Pedro Prados and Media Screen Media Homepage photo by Julio Rodríguez. |

Author

BIO: Bruce Broughton is best known for his many film scores, which include Silverado, Tombstone, The Rescuers Down Under, The Presidio, Miracle on 34th Street, the Homeward Bound adventures and Harry and the Hendersons. His television themes include JAG, Steven Spielberg’s Tiny Toon Adventures and Dinosaurs. His scores for television range from mini-series like Roughing It and The Blue and Gray to TV movies (O Pioneers!, Warm Springs) and countless episodes of television series such as Dallas, Quincy, Hawaii Five-O and How the West Was Won. With 24 nominations, he has won a record ten Emmy awards. His score to Silverado was Oscar-nominated, and his score to Young Sherlock Holmes was nominated for a Grammy. His music has accompanied many of the Disney theme park attractions throughout the world. His score for Heart of Darkness was the first recorded orchestral score for a video game. As a concert composer, ensembles such as the Cleveland Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony, the National Symphony and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra have performed his works with great success. His works for wind ensembles, bands and chamber groups have been performed and recorded throughout the world. He is a board member of ASCAP, a former governor of both the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, as well as a past president and founding member of The Society of Composers and Lyricists. He is an adjunct professor in Scoring for Motion Pictures and Television for the Thornton School of Music at USC and a lecturer in music composition at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music (Source www.brucebroughton.com).

Official website: |

These pieces, like the movie pieces become popular, some of these pieces become popular too, “Oliver’s Birthday”, the trumpet piece is a very popular trumpet piece, my Tuba Sonata is very very very popular, particularly at Universities played by the students, my piccolo concerto is popular, so I hear from people to play these things all through the world, every once in a while they get recorded, played by people I don’t know, haha, it is pretty nice, it feels good.

These pieces, like the movie pieces become popular, some of these pieces become popular too, “Oliver’s Birthday”, the trumpet piece is a very popular trumpet piece, my Tuba Sonata is very very very popular, particularly at Universities played by the students, my piccolo concerto is popular, so I hear from people to play these things all through the world, every once in a while they get recorded, played by people I don’t know, haha, it is pretty nice, it feels good. There was a division of everything, we collaborated…, actually, if you look at the credits, everything is equally credited, like Lennon & McCartney, you can’t tell who did what, sometimes I finished a piece and I wrote an e-mail to John and I said -Ok, I am done with this piece and I finished in the key of “C”-, and John said: -Ok, great, I start my new piece in the key of “C”-. Or he said to me: -Ok, I am done with this, and this, and this, and this, can you handle the next ones?-. So I would do the next ones.

There was a division of everything, we collaborated…, actually, if you look at the credits, everything is equally credited, like Lennon & McCartney, you can’t tell who did what, sometimes I finished a piece and I wrote an e-mail to John and I said -Ok, I am done with this piece and I finished in the key of “C”-, and John said: -Ok, great, I start my new piece in the key of “C”-. Or he said to me: -Ok, I am done with this, and this, and this, and this, can you handle the next ones?-. So I would do the next ones. Well, I get an interview, I read the script, and I liked the script, it was what I call a dense script, meaning it was very complicated and full of… you know, it was very well workout. And in this meeting, which should have last about twenty minutes, well, it actually last one hour and a half. We got along very well and our understanding of the story, which he had written with his brother, our understanding of the story was similar, which it is what a director is looking for, you must be sure the composer undertands what he is trying to do, because the only reason music is there is to help the story, so if the composer really doesn’t understand the story he shouldn’t be working in the movie.

Well, I get an interview, I read the script, and I liked the script, it was what I call a dense script, meaning it was very complicated and full of… you know, it was very well workout. And in this meeting, which should have last about twenty minutes, well, it actually last one hour and a half. We got along very well and our understanding of the story, which he had written with his brother, our understanding of the story was similar, which it is what a director is looking for, you must be sure the composer undertands what he is trying to do, because the only reason music is there is to help the story, so if the composer really doesn’t understand the story he shouldn’t be working in the movie. He kept saying that, he looked at me and said: -I really like the score-. I think Barry hired me because I just came up with Silverado. Silverado was a great deal, I didn’t realized at the time that Silverado was making me well known. So, we had a meeting, and we worked on it, I played him my themes on the piano, and he was polite, but not really taking them with him, you know, until he heard them with the orchestra. When he heard them with the orchestra he liked them a lot.

He kept saying that, he looked at me and said: -I really like the score-. I think Barry hired me because I just came up with Silverado. Silverado was a great deal, I didn’t realized at the time that Silverado was making me well known. So, we had a meeting, and we worked on it, I played him my themes on the piano, and he was polite, but not really taking them with him, you know, until he heard them with the orchestra. When he heard them with the orchestra he liked them a lot. And my wife, Belinda, was playing in the orchestra, that was the first time I saw her. So I have a lot of reasons why this was a really nice session. It all worked really well, Barry was really great to work with, he made really good movies, this is a really good movie, the music turned out well.

And my wife, Belinda, was playing in the orchestra, that was the first time I saw her. So I have a lot of reasons why this was a really nice session. It all worked really well, Barry was really great to work with, he made really good movies, this is a really good movie, the music turned out well. No, no, it is a style I like a lot, that was a very special style, that was a style that it has been made or invented by Carl Stalling, who originally worked for Walt Disney, and then he went over to Warner Brothers, and he did all those famous Bugs Bunny cartoons, the Looney Toons cartoons, and they were trying to mimic his style, Carl’s style, and my job was to be the supervising composer and pick all the composers who could do all the jobs. So I had 27 composers that I hired, I did about ten or eleven episodes myself, I wrote the theme…

No, no, it is a style I like a lot, that was a very special style, that was a style that it has been made or invented by Carl Stalling, who originally worked for Walt Disney, and then he went over to Warner Brothers, and he did all those famous Bugs Bunny cartoons, the Looney Toons cartoons, and they were trying to mimic his style, Carl’s style, and my job was to be the supervising composer and pick all the composers who could do all the jobs. So I had 27 composers that I hired, I did about ten or eleven episodes myself, I wrote the theme… That is a combination of Roger Rabbit, Tiny Toons, and I think that a movie I did for Peter Hyams, Stay Tuned, I think that was on that CD as well.

That is a combination of Roger Rabbit, Tiny Toons, and I think that a movie I did for Peter Hyams, Stay Tuned, I think that was on that CD as well. Yeah, yes. In that one we had to sound like other (previous) music. There is a piece to sound like Star Trek, a piece to sound like famous television shows…

Yeah, yes. In that one we had to sound like other (previous) music. There is a piece to sound like Star Trek, a piece to sound like famous television shows…

No hay comentarios