|

«I was always very open to new sounds» -Firstly, we would love to know about your starting point with music, you began practicing piano at a very early age (Helene Mirich was your teacher at that time), and we have read, you loved to improvise from the very first lesson, becoming a jazz pianist later. Please tell us about those first steps with music, and also about your idols at that time, like Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans or Hampton Hawes and their inspiration in your future music. As I got older I became interested in jazz piano. I loved listening to the recordings of Thelonious, Art Tatum, Earl Shearing, Oscar Peterson, Hampton Hawes, and Bill Evans. I was lucky that there was a club in Los Angeles called «Shelly’s Manhole» owned by the famous drummer Shelly Mann. I was able to go, accompanied by my father (as I was underage), to the club and see many of my idols. At that age I was totally naive and unaware that many of them were drug addicts… but they sure could play! -You said once that your musical education has been sort of backwards, I am quoting you here: “The first piece of classical music I ever studied was Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and that was because I read about it in Leonard Bernstein’s book The Joy of Music, I have done it backwards, haha, `Joplin to Gershwin to jazz to Stravinsky’.» Please, tell us about your next step, joining a jazz quartet as well as a rock cover band, and proclaiming the world your love for The Rolling Stones & The Beatles. I believe the first time I actually composed a song was when I was round 14. I was at a summer camp and could entertain the kids playing ragtime on a beat-up old upright piano. A camp counselor, hearing me play (and I was really good), asked me why didn’t I try to write something of my own. I had never even thought of that! What a great idea! So I did just that and that started it all. I was writing songs all through my high school years. When I was just beginning high school the Beatles and the Stones came on the scene and for the first time I fell in love with rock music. I started playing all their tunes. I was also in two bands, one that played rock covers, the other a jazz quartet. I think I loved the Beatles because even at that early period they were writing smart, sophisticated music. Also they incorporated English music hall music into their tunes. They were a huge influence on me and all through college I wrote songs mostly in that style. I would say that my three biggest influences were Leonard Bernstein (especially «West Side Story»), Stravinsky, and the Beatles. -You enrolled at Brandeis University in Boston and your ambition was to become some sort of artist, composing four musicals at that time and becoming more and more interested in the musical world. Taking even a class in orchestration from experimental composer, Alvin Lucier, «He not only taught me how to write for all the conventional instruments, but how to listen and create sounds from everything around me, and how to be completely open as to what ‘music’ means», please tell us about this experience. I became a studio arts major and did lots of printmaking, drawing, painting, and sculpture. I also continued writing songs every day and ended up composing the music for four original musicals. Somewhere during that time my advisor suggested that I change my major to music. I tried a couple of classes but hated the academic approach to music. Also, I was in beginning harmony but I had been playing Bill Evans since I was 8 years old… and listening to Stravinsky! So I found the classes boring and pedestrian and I remained an art major. -You were awarded both «Best Drama» and «Best Music» awards from Brandeis, and you received a Watson Foundation Fellowship which allowed you to live in London for a year and write music. During that time you wrote pop songs and worked on musicals, and I have read your intentions were to become a songwriter?. Tell us about your next collaborations with artists like Dirk Hamilton, Rod Taylor or Emmylou Harris and your friendship relation with producer Charles Plotkin. Being awarded the Watson Foundation Fellowship gave me the year of freedom I needed to become a good writer. I was located about an hour outside of London in Essex and spent every day writing songs and then going into London to meet with other musicians. By the time my year was over and I returned to Los Angeles I felt very confident of my writing ability and for the first time began to try to make a career out of music. This year of freedom from school and finances gave me a deep belief in my own talent. By the time I came back to LA I was ready to go. My family was friends with Chuck Plotkin’s family and so I went over to him when he was building Clover Studio in Hollywood. I was then writing and playing songs with my brother, Mark and performing as The Safan Brothers. Chuck started recording us and we became part of that group of singer/songwriters at Clover. I was also doing anything I could to make a living. Besides working part-time at my father’s jewelry store (which I hated) I also got a few jobs arranging songs on records by Dirk Hamilton, Rod Taylor (who Chuck was producing), and Emmylou Harris. -At that time, you became part of Plotkin’s group of singer-songwriters and you knew Wendy Waldman (daughter of composer Fred Steiner), Andrew Gold (son of film composer Ernest Gold) or Peter Bernstein (son of Elmer Bernstein). Also around the studio were people like Linda Ronstadt or Jennifer Warnes (who you played piano for). Tell us some anecdotes about that time, please, and the influence of it in your future career. -My brother and I, the Safan Brothers, didn’t ever get very far. We recorded lots of demos and wrote songs and played around LA, but never got signed by a label. My brother was going with Jennifer Warnes at the time and so I ended up playing piano in her band for a while. One of my songs, «Faces In The Wind», was recorded by another of Chuck Plotkin’s artists, Karla Bonoff. Also, part of the Clover group included Kenny Edwards who played bass for Linda Ronstadt so I was able to hang out with her as well. I learned a great deal being around the studio while she recorded some of her hit songs. However, my songwriting was really too broad and eclectic for hit records. My songs sounded more like symphonies than top-ten. -We are telling you now three names, Fred Steiner, Ernest Gold and Elmer Bernstein. They are, each in different ways, very important in your career and maybe they became your mentors, please, share with us your thoughts about the importance of their legacy in your work and how they helped you with their guidance and advice. Fred Steiner was the most scholarly of these composers who helped me. I learned a huge amount about film music and how it worked in a film and also all the practical issues of synching music to film. The moment I remember most is when Fred invited me over to his house to view «King Kong». He had it on a 16mm projector. He also had the original musical sketches for the film by the great composer Max Steiner (no relation to Fred) As we watched the film we were able to follow along with the score as written in Steiner’s own handwriting! What an amazing experience that was. A true education in great scoring. Also, when I got the «Bad News Bears In Breaking Training» Fred found me a private conducting teacher so I could lead the orchestra. Again, I seemed to learn everything as I needed it. Ernest Gold was very kind and encouraging. He offered to give me lessons in composition (which I never had as I skipped over music school). I spent many afternoons showing him my work and my development of themes. I really got my first lessons in classic composition from him. He was a master, a child prodigy from Austria who had to leave because of Nazi prosecution. His son, Andrew, was one of the most talented musicians I’ve ever known. On many of the Linda Ronstadt albums he played piano, drums, guitar, and sang back-up vocals. Elmer was also quite generous to me. He invited me to attend his recording sessions. I learned a huge amount about how music can clarify a scene in a movie watching him score «The Shootist» (John Wayne’s last film). I also learned a lot about the politics of film music from watching him deal with a difficult producer on that same film. Elmer and I also had the same agent and when he was offered a small film that he didn’t want to do, he helped me get the film. That was «Tag: The Assassination Game» by Nick Castle who I went on to compose many films for. I noticed the other day that I got into the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences in 1984 and that my two sponsors were Elmer and Ernest. I guess I was a pretty lucky young composer! -Your film music debut was in a never released project with famous director John McTiernan, called «The Demon’s Daughter», you said about it that you were hooked and loved the freedom to put together all your talents, from the dramatic writing of theater, to the melodic and rhythmic world of songs, to the esoteric world of contemporary classical music. It just suddenly all came together at that moment.”. Was this maybe your moment of truth, when you knew this would be your path? -One day when I was working selling jewelry I got a call from an old college friend. She said she had married this guy, John McTiernan, and they had just come to Los Angeles so John could attend AFI (American Film Institute). Also, he had made a super-16mm horror film and did I know anyone who could put music to it? I immediately said I’d do it and that was the actual start of my career as a film composer. -Your early experience with Mr. Lucier helped you to create some of your scores, like «Stand and Deliver», where you created an entire percussion library from found objects, or «Wolfen», where you experimented with new composition techniques. Please, share with us the story behind the composition of these scores, and the sad situation that ended with the second one being replaced at the end (as Jerry Goldsmith or Alex North said, you are not a film music composer per se until you have had one of your scores rejected). -I was told it was Miklós Rósza who said that! Unfortunately it seems to happen to everyone. -What do you remember of the composition of «Fade To Black» and the creation of the score for this original film, especially in the time he was produced, a dark thriller with the cinema itself as a protagonist, what can you tell us about the collaboration with the director in this film? I never had any collaboration with, or even met, the director of «Fade To Black». At the point when I was hired the producers had taken over the post-production of the film from him, so I was totally on my own. I wanted to combine synthesizers with a little bit of traditional lavish Hollywood film music (as the film was about the old classic films). I also was interested in extremely close miking of the instruments so one would feel like they were sitting inside of a harp or cello or piano. It was a pretty complicated job to combine all these sounds… strings, synths, close miked piano and harp and percussion/drums… but I really like the score even now. It feels Hollywood but also very creepy and just off the center. My memory is that it was really a fun film to score and record and, at the time, I felt like I was in new territory. -We would like to know about the creation of the jazzy and nourish comedy thriller, «Tag: The Assassination Game», how were you attached to the project and how do you decided the approach to the music? -We would love to know about the stories and anecdotes of the process of creation that could be found behind such iconic scores as «Son of the Morning Star», «The Last Starfighter» and «Remo Williams» Please, could you share with us how were you attached with these projects and how was your collaboration with directors and producers achieving the final unforgettable scores? What about the lyrical beauty of «Son of the Morning Star»: -An about the sweeping orchestral spectacle of «The Last Starfighter»? Centauri, played by Robert Preston, was a great character… especially as «The Music Man» was one of my favorite musicals (he was the star of the film). I wrote a sort of snake charmer theme on the EWI. Again, I used both synth and aleatory orchestral music for the action scenes with the Hit Beast. But the core of the music is the «heart theme», from the very sparse, small version to the huge full orchestra one. To me, this theme portrays adventure, humor, longing, and hope. Maybe that’s why it seems to have lived on for so long. -And the thrilling action and rhythm and gorgeous eastern melodies of «Remo Williams»: Again, during that time the pressure to be like «Star Wars» or «Indiana Jones» was upon us all. I did write a big adventure theme for Remo but added lots of big electronic drums and even gun shots! His quieter theme was performed mostly on synthesizers. For the character of Chiun, a Korean Martial Arts Master, I went to the UCLA Ethnomusicology Library and studied Korean music. Luckily there is a very large Korean population in Los Angeles and I was able to hire a Korean orchestra to play on the score. By the time we were recording we were on two 24-track machines slaved together to form 48 tracks of Synclavier (this was all pre-digital), full symphony orchestra, and small Korean orchestra. With ethnic musicians playing with conventional classic musicians plus music machines and electronic percussion, the tuning and timing problems were immense. It was quite an ambitious undertaking! There were layers and layers of percussion underneath the orchestra and topped with the strange Korean sounds. Chiun’s Theme is based on a Korean folksong and is played as a yearning melody at the beginning and then as a Viennese waltz at the end of the film. -What can you remember of your addition to the «Elm Street» franchise with your score for the fourth installment, working with director Renny Harlin? -I got the job because Bob Shea, the president of New World Pictures saw «Remo» and loved the score. It was fun working with Renny Harlin. He could really eat and drink immense amounts at lunch and seem unscathed. I think it was his youth in the winter weather of Finland. He was sort of like a Viking… a very charming and good guy to work for. The score to «Elm St.» was done totally with synthesizers in my studio. I tried to make it as colorful as possible and both scary and fun at the same time. I also occasionally used Charles Bernstein’s great theme. -About you heartfelt and jaunty scores for comedies like «Major Payne» or «Mr. Wrong», what can you tell us about this particular genre of scoring and how do you prefer to approach to it, specially focusing in these two compositions. -These were two more films with Nick Castle. «Major Payne» was a very funny military comedy starring Damon Wayans. The music is pretty straight-ahead «military fun marches». I think the film was originally tracked with «The Great Escape» by Elmer Bernstein. This classic type of Hollywood film scoring played well against the over-the-top comedy of Damon. Added to that mix was lots of hip-hop drums and percussion. I’ve done lots of comedy («Cheers», etc) and I find that it’s often good to play against the comic elements with very straight music that just slightly off-center. My favorite cue is «Bedtime Story» in which Payne tells a story to a little kid, starting out with the classic children’s story «Little Engine That Could» and ending up telling an intense Vietnamese War horror story. Really funny! I really enjoyed writing the music and being able to give a nod to Elmer’s great score. -You have created a lot of scores for television, being maybe the most famous the show that provided you the ASCAP Film and Television Award for scoring a “Top TV Series” seven years in a row, 1988-1994, for «Cheers». In 1991 you were nominated too for an Emmy for Outstanding Achievement in Music and Lyrics for the TV series «Life Goes On» (1989), shared with Mark Mueller (lyricist). But you have also worked for «Amazing Stories», «The New Alfred Hitchcock Presents», «The Twilight Zone»… what can you share with us about all these shows and scores that all of the people of my age have grown watching and listen to them with delight through the last decades? (maybe some anecdotes about the production of your work with some of the amazing filmmakers that collaborated with you in them). «Life Goes On» was near to my heart as it was the first television show that had a major character with a disability (Down Syndrome) actually being played by an actor with the same disability. Since I have a son with Down Syndrome I really wanted to be the composer of the show. To get the job I didn’t even call my agent, but cold-called the producer and got the gig over the phone. Also, Patti Lupone was cast as the mother and I reminded the producer that she was an amazing singer (she was «Evita» on Broadway). Thereafter she was given a back story where she could sing and we recorded many songs together. Also, I wrote the songs (with Mark Mueller) for a musical episode of the show in which Leon Redbone sang seven of our original compositions. One, «The Bittersweet Waltz», received an Emmy nomination. I’m still good friends with Chris Burke, the lead of the show. Not much to say about «Twilight Zone» or «Amazing Stories». On the episode of «Twilight Zone» I wrote for John Milius he told me to write music for every second of the entire film and he would decide later what he wanted to actually use… that was a first! On the episode of «Amazing Stories» I wrote with Danny DeVito directing, Steven Spielberg made us add more music after it was recorded. Danny came from half-hour television like «Taxi» and «Cheers» where almost no music was used and we had therefore put way too little music in his episode. Steven, on the other hand, was of the «more music, please» school of filmmaking… so I wrote more!, haha -In recent years you have returned to composing for theater, though remaining active in scoring for film and television as your time allows. We would love to focus now in your work for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. immersing yourself in the world of dare-devilry, superhuman stunts, and performing beasts, what can you share with us about this particular and the joy and difficulties to provide music for this world? The process is like a mash-up of film and theater. You are writing for a live act and therefore, unlike a film, it is slightly different each performance, so the music must be very flexible and is played by a live band (with lots of electronics). Also, the music is written (and there is lots and lots of music!) in the months before the actual rehearsals begin. So when the show is finally put together in rehearsals there are constant changes and revisions. I have an entire music department that stays up all night making the changes of the day before! It’s a huge show with almost 200 people and plays in gigantic indoor stadiums so it is quite a feat getting it up and running. Also, the performers are from all over the world, so everyone tends to speak a different language and there are Spanish, Russian, and Chinese translators on hand to help the director. To fill up the huge arenas and drive the circus, the music must be extremely percussive and aggressive. The music is truly propelling this huge beast. Fun to write if at times exhausting. -Could you share with us some information about possible new CD releases of your scores in the near future, specially that so much requested complete edition of «The Last Starfighter» people are claiming for a long time?, could that be true? 😉 -Since I don’t own the music copyrights or master recordings I’m not really involved with the CD releases. I really don’t know how many are planned. However, I have heard from the folks at Intrada that they are planning a completely new release of «The Last Starfighter» using the original master recordings. Also, they are trying to release a double CD that would, for the first time, have the complete score of «Son of the Morning Star». Also, I believe that Robin Esterhammer of Perseverance Records is trying to acquire the rights to «The Legend of Billie Jean». I would love for that score to be released for the first time. However, I have no idea when any these might be released! -Please, could you share with us some news about your nearer future and maybe some upcoming projects you were allowed to tell us about? -Mr. Safan, you have been announced as New Official Guest of the Tenth Anniversary of the International Film Music Festival Province of Córdoba, a very special edition for all involved celebrating 10 years of an event that has fond deeply in the film music fan world, are you excited to be part of this celebration of music with the attendants, through the concerts, signing sessions and panels?, can you advance us your impressions about the music we will be able to enjoy there Live in the concerts? -I am genuinely thrilled to be part of the Festival. I think it is a great honor to be able to perform some of the music I wrote and will be available for the entire week. I have also visited Spain many times before and even speak a bit of Spanish. I travelled through Andalucía and visited Cordoba just two years ago and will be glad to be back. Years ago I wrote an Overture from «The Last Starfighter» for the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra and it has been performed and recorded many times. But it is only 4 minutes long and I have always wanted to compose a more extensive suite. That is what I am working on now and will perform for the first time at the Festival. I am also planning to compose a short Overture from «Remo Williams» and also a short, very emotional, piece from «Son of the Morning Star». (Photos and audios used with permission from Craig Safan) |

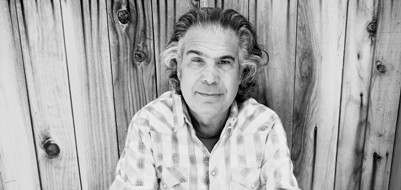

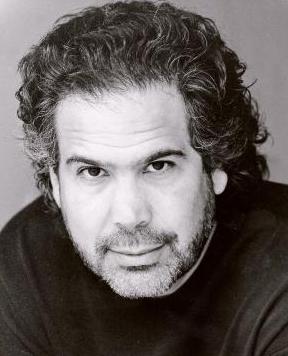

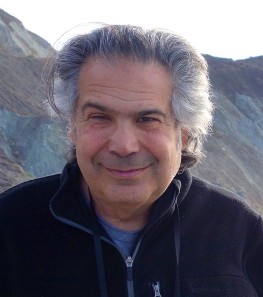

Author BIO: Craig Safan, film, television, theater, circus and song composer of great influence and importance during the last three decades, having created such iconic scores and compositions for cinema as Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins, Son of the Morning Star, The Last Starfighter, The Legend of Billie Jean, Tag: The Assassination Game, Major Payne, Mr. Wrong, Fade To Black, Stand and Deliver, o Nightmare on Elm Street IV: The Dream Child, television, Cheers, Life Goes On, Amazing Stories, The Twilight Zone, The New Alfred Hitchcock Presents, theater, & even the Greatest Show on Earth’s World, the circus, with different compositions for the Ringling Brothers or the Barnum & Bailey spectacles. The music and the composition world took him at a very early age, even creating musicals and songs at the age of eleven. Since he was at college and high school, he knew his future will be related to music no matter what, learning from his teachers, Helene Mirich (when he was a young boy) and Alvin Lucier (who opened up his world in terms of hearing everything as possible music) and masters inspiration like Thelonious Monk or Bill Evans, working with artists like Dirk Hamilton, Rod Taylor or Emmylou Harris, becoming a friend with producer Charles Plotkin and meeting Wendy Waldman (daughter of composer Fred Steiner), Andrew Gold (son of film composer Ernest Gold) or Peter Bernstein (son of Elmer Bernstein), creating The Safan Bros, a band with his brother, and collaborating with stars like Linda Ronstadt or Jennifer Warnes (who he played piano for), until finally having its cinema composing debut with the film The Demon’s Daughter, directed by the famous John McTiernan.

Craig Safan’s website: |

-My mother was a classical pianist and piano teacher from a very small town, Laredo, Texas. She met my father during WWII and they moved to Los Angeles. We always had a piano in our house and I would try to play it and pick out tunes when I was 4 or 5 years old. My first musical love was «honkey-tonk» and «ragtime» piano music… especially «Alexander’s Ragtime Band» by Irving Berlin and «Kitten on the Keys» by Zez Confreys. «Alexander’s Ragtime Band» was the first piece I picked out… my mother helped me. She was smart enough to realize that she shouldn’t be my teacher and found Helene Mirich who taught what at the time was called «popular» piano. That meant no classics, just pop tunes. However Helene was also a violinist and even though we were improvising from the very first lesson, she also gave me a strong musical background… but she used ragtime and jazz pieces rather than the classics or traditional Hanon exercises to build my technique. In those early years I played mostly standard tunes and ragtime. Half the lesson would be improvisation exercises and chord structures, then I could play the tunes.

-My mother was a classical pianist and piano teacher from a very small town, Laredo, Texas. She met my father during WWII and they moved to Los Angeles. We always had a piano in our house and I would try to play it and pick out tunes when I was 4 or 5 years old. My first musical love was «honkey-tonk» and «ragtime» piano music… especially «Alexander’s Ragtime Band» by Irving Berlin and «Kitten on the Keys» by Zez Confreys. «Alexander’s Ragtime Band» was the first piece I picked out… my mother helped me. She was smart enough to realize that she shouldn’t be my teacher and found Helene Mirich who taught what at the time was called «popular» piano. That meant no classics, just pop tunes. However Helene was also a violinist and even though we were improvising from the very first lesson, she also gave me a strong musical background… but she used ragtime and jazz pieces rather than the classics or traditional Hanon exercises to build my technique. In those early years I played mostly standard tunes and ragtime. Half the lesson would be improvisation exercises and chord structures, then I could play the tunes. My teacher and I would improvise on two pianos in her studio. Also, to improve my technique, she would transcribe the solos by Thelonious Monk or Bill Evans off the LP records and I would learn them note-for-note. At this point I don’t believe I had ever heard a classical symphony. However I did start loving the tunes from all the Broadway musicals… and that turned into a big part of my composing career.

My teacher and I would improvise on two pianos in her studio. Also, to improve my technique, she would transcribe the solos by Thelonious Monk or Bill Evans off the LP records and I would learn them note-for-note. At this point I don’t believe I had ever heard a classical symphony. However I did start loving the tunes from all the Broadway musicals… and that turned into a big part of my composing career. -My musical education was in a way backwards. When I was around 13 years old I read «The Joy of Music» by Bernstein and became fascinated with «The Rite of Spring». I got the LP and listened to it many times. When I was in college I bought the full score and studied Stravinsky’s orchestration. I had never really listened to Mozart or Beethoven at that point.

-My musical education was in a way backwards. When I was around 13 years old I read «The Joy of Music» by Bernstein and became fascinated with «The Rite of Spring». I got the LP and listened to it many times. When I was in college I bought the full score and studied Stravinsky’s orchestration. I had never really listened to Mozart or Beethoven at that point. -When I graduated high school I had no idea what I wanted to become. I knew I would never become a «businessman» like my father. That seemed a horrible life to me. However, in addition to being a very good pianist by that time, I had always been able to draw and paint. I was even art editor of my yearbook and designed all the typefaces by hand! But I couldn’t very well tell my parents that I wanted to become an artist… so I entered a liberal arts university and told them I was thinking of eventually becoming and architect, a profession that they could understand.

-When I graduated high school I had no idea what I wanted to become. I knew I would never become a «businessman» like my father. That seemed a horrible life to me. However, in addition to being a very good pianist by that time, I had always been able to draw and paint. I was even art editor of my yearbook and designed all the typefaces by hand! But I couldn’t very well tell my parents that I wanted to become an artist… so I entered a liberal arts university and told them I was thinking of eventually becoming and architect, a profession that they could understand. Also at that time I became interested in synthesizers and electronic music. There was an electronic music lab at Brandeis and I talked my way into being able to use it (even though I wasn’t a music major). It was a Buchla System (Moog was the other one at the time) and I spent thousands of hours playing in what to me was a giant sandbox! I loved generating and altering sounds and would spend all night plugging in cords to see what sounds would appear. These were the early days of synths and it was virtually impossible to even tune them. They were built to create sounds, not for Western pop music… that came much later. Because of all my time spent in the electronic studio, when the synthesizer revolution came many years later in pop and film music I was ready. I was totally comfortable and happy to use and play with synthesizers. I even owned a Synclavier. In those days a 10 meg hard drive cost $10,000! I think the film «Warning Sign» was one of the first films that used only synthesizers. I composed and recorded it in my studio only using a Synclavier.

Also at that time I became interested in synthesizers and electronic music. There was an electronic music lab at Brandeis and I talked my way into being able to use it (even though I wasn’t a music major). It was a Buchla System (Moog was the other one at the time) and I spent thousands of hours playing in what to me was a giant sandbox! I loved generating and altering sounds and would spend all night plugging in cords to see what sounds would appear. These were the early days of synths and it was virtually impossible to even tune them. They were built to create sounds, not for Western pop music… that came much later. Because of all my time spent in the electronic studio, when the synthesizer revolution came many years later in pop and film music I was ready. I was totally comfortable and happy to use and play with synthesizers. I even owned a Synclavier. In those days a 10 meg hard drive cost $10,000! I think the film «Warning Sign» was one of the first films that used only synthesizers. I composed and recorded it in my studio only using a Synclavier. -By the time I graduated university I knew I would never become an architect. I was too worried I’d get stuck in some large firm designing closets. I thought I’d like to be a songwriter or an arranger. I had arranged the strings on a couple of songs while in college and I liked doing it.

-By the time I graduated university I knew I would never become an architect. I was too worried I’d get stuck in some large firm designing closets. I thought I’d like to be a songwriter or an arranger. I had arranged the strings on a couple of songs while in college and I liked doing it. -Serendipitously, three of the musicians who I had been working with at Clover Studios had all gone to high school together and had fathers who were film composers: Wendy Waldman (Fred Steiner), Andrew Gold (Ernest Gold), and Peter Bernstein (Elmer Bernstein). When I scored the «Demon’s Daughter» for John McTiernan I immediately knew that I had found something I loved and that matched my talents, and I pursued it full force. I started visiting my friends’ fathers and they became my mentors.

-Serendipitously, three of the musicians who I had been working with at Clover Studios had all gone to high school together and had fathers who were film composers: Wendy Waldman (Fred Steiner), Andrew Gold (Ernest Gold), and Peter Bernstein (Elmer Bernstein). When I scored the «Demon’s Daughter» for John McTiernan I immediately knew that I had found something I loved and that matched my talents, and I pursued it full force. I started visiting my friends’ fathers and they became my mentors. I think I was always very open to new sounds, whether they were produced by conventional instruments or electronic ones, or ones that I made. In «Stand and Deliver» I wanted to have a general Latin sound…. but not specifically of one Latin country. So I took all the ethnic percussion and recreated those sounds using objects like huge water bottles and steel bolts and whatever else I found. I sampled them all on the Synclavier and then combined them with a synth score, real guitars and real Peruvian flutes.

I think I was always very open to new sounds, whether they were produced by conventional instruments or electronic ones, or ones that I made. In «Stand and Deliver» I wanted to have a general Latin sound…. but not specifically of one Latin country. So I took all the ethnic percussion and recreated those sounds using objects like huge water bottles and steel bolts and whatever else I found. I sampled them all on the Synclavier and then combined them with a synth score, real guitars and real Peruvian flutes. On «Wolfen» the problem was that the director wanted a very avant-garde score in which we actually developed the language of the supernatural wolves, and the producer wanted a romantic John Williams score… and they weren’t talking to each other! It was a very bad political situation and I was in the middle and chose to follow the director… the wrong choice. On the musical side I was a big fan of Penderecki and I was hanging out at some of John Corigliano’s sessions for «Altered States» and thought I’d try a big score with no electronics but just weird sounds that came from the traditional orchestra. I worked privately with each player to see just how weird they could be and wrote out the entire score «aleatory»… meaning instead of specific notes there were «events» that created the music. I was really happy when Intrada Records released my original score a few years ago.

On «Wolfen» the problem was that the director wanted a very avant-garde score in which we actually developed the language of the supernatural wolves, and the producer wanted a romantic John Williams score… and they weren’t talking to each other! It was a very bad political situation and I was in the middle and chose to follow the director… the wrong choice. On the musical side I was a big fan of Penderecki and I was hanging out at some of John Corigliano’s sessions for «Altered States» and thought I’d try a big score with no electronics but just weird sounds that came from the traditional orchestra. I worked privately with each player to see just how weird they could be and wrote out the entire score «aleatory»… meaning instead of specific notes there were «events» that created the music. I was really happy when Intrada Records released my original score a few years ago. -As I explained above, I got «Tag» because Elmer Bernstein really didn’t want to do it and somehow convinced the producers and director (Nick Castle) that I was the guy. This was the beginning of my relationship with Nick Castle. We went on to do many films together and become good friends. He had created this film that was a contemporary noir thriller and was filmed quite lusciously, almost like an old Bogart film with Linda Hamilton filling in for Lauren Bacall. But, not unlike «Fade To Black», I didn’t just want to mimic the old film scores so I combined the beautiful Hollywood sounds of romance and jazz (sort of David Raksin) with the evil, weird sounds of a very modern orchestra. This was another of my attempts at a hybrid musical score. I just heard it again when the CD was recently released and I really like the energy of the main title. That was all recorded live… no overdubs!

-As I explained above, I got «Tag» because Elmer Bernstein really didn’t want to do it and somehow convinced the producers and director (Nick Castle) that I was the guy. This was the beginning of my relationship with Nick Castle. We went on to do many films together and become good friends. He had created this film that was a contemporary noir thriller and was filmed quite lusciously, almost like an old Bogart film with Linda Hamilton filling in for Lauren Bacall. But, not unlike «Fade To Black», I didn’t just want to mimic the old film scores so I combined the beautiful Hollywood sounds of romance and jazz (sort of David Raksin) with the evil, weird sounds of a very modern orchestra. This was another of my attempts at a hybrid musical score. I just heard it again when the CD was recently released and I really like the energy of the main title. That was all recorded live… no overdubs! -I don’t remember exactly how I was attached to this «Son of the Morning Star», but I loved doing it. This was a mini-series about Custer and Little Bighorn and all of the Native Americans were played by Native Americans. A huge amount of effort went into making the film realistic and true. I wanted to separate the music into two distinct parts: that of the U.S. Americans and that of the Native American Tribes. I chose to use a largely string-based, tonal orchestra for the U.S. Americans. It was very melodic and emotional with solo trumpet, horn, trombone, and a few woodwinds. No synthesizers. The Native American music was a Native American flute and Native American percussion, all on a bed of synthesizers. It was largely improvised and based on traditional melodies. I wanted the two types of music to be separate entities. I felt the huge battle scenes and massacres were incredibly sad and so I scored most of them with slow, emotional melodies. There is very little pure action music. I wanted to portray the subtext, which was the tragic side of the Westward Expansion. There are some military themes, but no really heroic ones. It’s all about loss and sadness. On the other side I chose traditional Native American melodies for the appropriate scenes and had a Native American flute player improvise on them while watching the scenes. Then I re-cut all the flute music and added an amorphous pad of synthesizers. On top of that I overdubbed Native American percussion to hit exact spots and cuts in the film. This is still one of my favorite scores in its pure emotionality, the beauty of the orchestral playing, and the depth of the melodies. It’s definitely my wife’s favorite!

-I don’t remember exactly how I was attached to this «Son of the Morning Star», but I loved doing it. This was a mini-series about Custer and Little Bighorn and all of the Native Americans were played by Native Americans. A huge amount of effort went into making the film realistic and true. I wanted to separate the music into two distinct parts: that of the U.S. Americans and that of the Native American Tribes. I chose to use a largely string-based, tonal orchestra for the U.S. Americans. It was very melodic and emotional with solo trumpet, horn, trombone, and a few woodwinds. No synthesizers. The Native American music was a Native American flute and Native American percussion, all on a bed of synthesizers. It was largely improvised and based on traditional melodies. I wanted the two types of music to be separate entities. I felt the huge battle scenes and massacres were incredibly sad and so I scored most of them with slow, emotional melodies. There is very little pure action music. I wanted to portray the subtext, which was the tragic side of the Westward Expansion. There are some military themes, but no really heroic ones. It’s all about loss and sadness. On the other side I chose traditional Native American melodies for the appropriate scenes and had a Native American flute player improvise on them while watching the scenes. Then I re-cut all the flute music and added an amorphous pad of synthesizers. On top of that I overdubbed Native American percussion to hit exact spots and cuts in the film. This is still one of my favorite scores in its pure emotionality, the beauty of the orchestral playing, and the depth of the melodies. It’s definitely my wife’s favorite! –«The Last Starfighter» was my next collaboration with Nick Castle after «Tag». It was a huge space opera full of hope. All the special effects were done on computers, I believe the first such film to do so. The producers, of course, wanted a score that sounded like «Star Wars» and there was no way to go against that and survive. So, where the «Star Wars» score was largely influenced by Holst’s «The Planets» (which was the piece Lucas had tracked the film with) I decided to listen to Mahler and Sibelius. I’m not sure if that really made much of a difference to the average listener, but it did to me as a composer as it freed me from John Williams! Also, I was able to use a huge, Mahlerian orchestra with quadruple woodwinds and six trumpets and horns. I also added a synth and an EWI (electronic woodwind instrument) into the mix.

–«The Last Starfighter» was my next collaboration with Nick Castle after «Tag». It was a huge space opera full of hope. All the special effects were done on computers, I believe the first such film to do so. The producers, of course, wanted a score that sounded like «Star Wars» and there was no way to go against that and survive. So, where the «Star Wars» score was largely influenced by Holst’s «The Planets» (which was the piece Lucas had tracked the film with) I decided to listen to Mahler and Sibelius. I’m not sure if that really made much of a difference to the average listener, but it did to me as a composer as it freed me from John Williams! Also, I was able to use a huge, Mahlerian orchestra with quadruple woodwinds and six trumpets and horns. I also added a synth and an EWI (electronic woodwind instrument) into the mix. I was looking for what I would call a «heart theme»… a theme that just didn’t portray the protagonist, but actually spoke to the core of the film. I thought about it for a while and remember driving in Hollywood one day and the melody coming to me. While stopped at a traffic light I quickly jotted down the theme and that was it. It worked for the slow, romantic, wistful moments as well as for the big exciting, heroic ones.

I was looking for what I would call a «heart theme»… a theme that just didn’t portray the protagonist, but actually spoke to the core of the film. I thought about it for a while and remember driving in Hollywood one day and the melody coming to me. While stopped at a traffic light I quickly jotted down the theme and that was it. It worked for the slow, romantic, wistful moments as well as for the big exciting, heroic ones. –«Remo» is probably the most complicated score I ever wrote and is the culmination of many earlier scores that combine a large orchestra, ethnic instruments, and lots of synthesizers. This is a very difficult combination of sounds and instruments to combine together and my thanks go to Dennis Sands, who recorded and mixed the score.

–«Remo» is probably the most complicated score I ever wrote and is the culmination of many earlier scores that combine a large orchestra, ethnic instruments, and lots of synthesizers. This is a very difficult combination of sounds and instruments to combine together and my thanks go to Dennis Sands, who recorded and mixed the score. «Mr. Wrong» was a very difficult film and experience. I think the hardest genre of film to make is the black comedy… meaning funny and dark at the same time. It’s very hard to get audiences to go along with that and the successful examples are few («Harold and Maude», «Dr. Strangelove» come to mind). The film was tracked with music by the Mexican composer Esquival. I helped with the tracking as I’m a big fan of his wacky 1960’s sounds. This score was one of the most fun to actually compose as I could play with all the sounds of both Esquival and Henry Mancini… jazz, Latin, Aaron Copland. I had a great orchestra with lots of fantastic musicians and we all had a great time recording the music. The hard part was the political side of the film… and every film has a political side. The studio just wasn’t really behind the film. They had wanted a simple, romantic vehicle for Ellen DeGeneres and they were getting this wild, dark comedy with kidnapping and gunplay and drugs. Also, this was when Ellen was coming out to the world as a lesbian, so the romantic bit didn’t really work! Great experience musically, horrible experience politically.

«Mr. Wrong» was a very difficult film and experience. I think the hardest genre of film to make is the black comedy… meaning funny and dark at the same time. It’s very hard to get audiences to go along with that and the successful examples are few («Harold and Maude», «Dr. Strangelove» come to mind). The film was tracked with music by the Mexican composer Esquival. I helped with the tracking as I’m a big fan of his wacky 1960’s sounds. This score was one of the most fun to actually compose as I could play with all the sounds of both Esquival and Henry Mancini… jazz, Latin, Aaron Copland. I had a great orchestra with lots of fantastic musicians and we all had a great time recording the music. The hard part was the political side of the film… and every film has a political side. The studio just wasn’t really behind the film. They had wanted a simple, romantic vehicle for Ellen DeGeneres and they were getting this wild, dark comedy with kidnapping and gunplay and drugs. Also, this was when Ellen was coming out to the world as a lesbian, so the romantic bit didn’t really work! Great experience musically, horrible experience politically. -That’s a big question! «Cheers» was like a side job to me for eleven years. There was very little music in each episode so I’d do several segments every few weeks. The most fun part of «Cheers» was coming up with the original sound of the show. I wanted it to sound like a mediocre acoustic bar band with a clarinet player that happened to sit in and also wasn’t very good. That sound worked from the first episode to the last! I think there were around 255 shows.

-That’s a big question! «Cheers» was like a side job to me for eleven years. There was very little music in each episode so I’d do several segments every few weeks. The most fun part of «Cheers» was coming up with the original sound of the show. I wanted it to sound like a mediocre acoustic bar band with a clarinet player that happened to sit in and also wasn’t very good. That sound worked from the first episode to the last! I think there were around 255 shows. -I’ve always loved musical theater. I could play pretty much every musical theater song by the time I was eleven. I was writing musicals all through college and even worked on a musical at the Public Theater in New York. I still have several musicals in development. As far as circus, when I was in high school my parents took me to Moscow and I saw the circus there, even making a little 8mm film of it… I was entranced. I never expected to actually write for it, but my agent in New York who handled my stage musicals also worked with Ringling Brothers and they were looking for someone who could write more expansive, orchestral music for their show. They heard «Starfighter» and were sold and I ended up writing five original circuses for them over the years.

-I’ve always loved musical theater. I could play pretty much every musical theater song by the time I was eleven. I was writing musicals all through college and even worked on a musical at the Public Theater in New York. I still have several musicals in development. As far as circus, when I was in high school my parents took me to Moscow and I saw the circus there, even making a little 8mm film of it… I was entranced. I never expected to actually write for it, but my agent in New York who handled my stage musicals also worked with Ringling Brothers and they were looking for someone who could write more expansive, orchestral music for their show. They heard «Starfighter» and were sold and I ended up writing five original circuses for them over the years. -My latest project will be a large composition that I have been thinking about writing for many years. I have always had a deep love of Paleolithic cave art and years ago visited many of the caves in France. I have wanted to write music based on my impressions of that prehistoric art for a long time. In April 2014 I will be travelling through France and Spain and visiting many of the caves and sites where early man lived. I will then start on the composition which will hopefully be released in 2015 on Perseverance Records.

-My latest project will be a large composition that I have been thinking about writing for many years. I have always had a deep love of Paleolithic cave art and years ago visited many of the caves in France. I have wanted to write music based on my impressions of that prehistoric art for a long time. In April 2014 I will be travelling through France and Spain and visiting many of the caves and sites where early man lived. I will then start on the composition which will hopefully be released in 2015 on Perseverance Records.

No hay comentarios