|

Versión en español

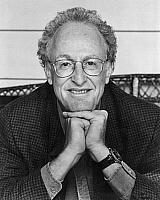

Born in Buffalo in 1937, David Shire's career as film and TV composer started in the 60's with the legendary TV serials The Virginian. Having also written scores for a good number of feature films, it's the musicals he's worked on in Broadway that he calls to have played the most relevant role. He was awarded with an Oscar for his song to the 1979 picture Norma Rae ("It Goes Like It Goes"). In addition he has earned a Grammy for his score to Saturday Night Fever and has further gained recognition, being several times nominated to the Emmys, Tonys, BAFTAs, etc.

He was married to Talia Shire, Francis Ford Coppola's sister, and is currently married to actress Diddi Conn. This long interview tries to shed some light on the many faces of this composer.

BSOSpirit (BS):

First of all, we would like to thank you for giving us the chance to carry out

this interview. We have to acknowledge that you are being considered as

a real cornerstone in film music. So this is indeed a great pleasure, a

wonderful privilege, to talk to you. We would then virtually start by asking

you about the way you began scoring music for films.

David Shire (DS): My father was also a musician, so I started

very soon writing incidental scores for plays in the college, and then went

to Broadway. A few tapes with my works reached a few people at Universal, and

they asked me to move to Los Angeles and begin a career as a TV series musician.

The first project was The Virginian, in 1962. Perhaps it would

have been more difficult to start in times like these, with so many young composers

asking for an opportunity in the film industry... I don’t know. This business

is constantly changing.

BS:  So, you started with The Virginian in television... How do you remember those days? So, you started with The Virginian in television... How do you remember those days?

DS: It was a very exciting turning point in my musical career. To be able to work for Universal meant for me a chance to encounter other composers, working together in recording sessions at the studio... It is a shame that no one works like that today; no more recordings at the studios. Composers work now in their own homes, missing the chance of a skilful interaction.

BS: Your first feature film in the big screen was Summertree (1971). The main character was played in that film by Michael Douglas, if I remember well... How did you take this step from TV to the big screen?

DS: I think that it is easier to score films. You are allowed to spend more time with the creative aspects (in TV you always need to rush). Sometimes there is also more budget, so you can use more resources. Technically, however, I don’t see any difference between writing a score for the TV or the big screen. All you have to do is to put music to a planned scene, fill a plot with a peculiar sound. In both situations you are asked to meet the director or some technical crew, creating an interaction.

BS: The 70s were really a very busy period for you. Between 1970 and 1974, when The Conversation was released, you were involved in quite a number of films, such as Two People, To Find a Man, Skin Game, Class of '44 or Showdown... Do you remember any particular title with a fondest pleasure?

DS: Skin Game was the best score I did then. Paul Bogart was the director, and I was able to use the largest orchestra I’ve ever worked with. I learnt as well many things about sound engineering. However, The Conversation might be considered as the most important film in that particular period. DS: Skin Game was the best score I did then. Paul Bogart was the director, and I was able to use the largest orchestra I’ve ever worked with. I learnt as well many things about sound engineering. However, The Conversation might be considered as the most important film in that particular period.

BS: I find quite remarkable how strongly you based your score of The Conversation in one single instrument: the piano. Why did you place so much emphasis on this instrument?

DS: Francis Ford Coppola discussed this with me. He wanted the sound of a piano, a score with an intimate and very simple intention. At first I was a little disappointed, but I must recognise now that Francis was right. This was the music that was needed.

BS:  The year 1974 saw you working in no less than eight projects on a row, both for film industry and TV. Two of your best scores, the already mentioned The Conversation and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three were written in that same year. Wasn’t it too much stressful? The year 1974 saw you working in no less than eight projects on a row, both for film industry and TV. Two of your best scores, the already mentioned The Conversation and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three were written in that same year. Wasn’t it too much stressful?

DS: I should say yes. It had to be stressful with all those deadlines in my head. But, you know, this is how it works. Some projects were so exciting that I even didn’t realize how stressful it was. I felt happy doing my job.

BS: The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is one of your most popular scores. It bears a main theme with an outstanding sense of rhythm. In a certain way, this music witnessed a certain period in score writing in which musicians such as Lalo Schifrin were defining a new style... If you were to score this film today, would you approach it in a different way?

DS: Yes, I think I would. When I wrote the score I did it in the right way then, but today films and scores are conceived with a different idea.

BS: Please, tell us something more about your experience in working out The Taking of Pelham One Two Three... The last scene with Walter Matthau has a perfect music match, and then rolls over the end credits in a remarkable way. How would you rate this score and what would you say was the real impact of it in terms of giving a boost to your professional career?

DS: The Taking of Pelham One Two Three was one of my best scores ever. The originality of it is not always achievable in any other score I wrote. It was certainly a quality mark in my career.

BS:  In 1975 you composed another widely recognised score: Farewell, My Lovely, a superb film based on a novel by Raymond Chandler, directed by Dick Richards and starring Robert Mitchum. Can it be considered another of the best films you've ever been involved in? In 1975 you composed another widely recognised score: Farewell, My Lovely, a superb film based on a novel by Raymond Chandler, directed by Dick Richards and starring Robert Mitchum. Can it be considered another of the best films you've ever been involved in?

DS: I don’t know. Nevertheless, it was a very good film, very entertaining. I thought about the score as homage to film noir, an opportunity to pay a tribute to this sort of music.

BS: Film Noir is a genre very well known because of the crucial role the music plays in it. How did you plan such a score?

DS: The style it required was already in my blood. I had a good jazz background in my training as a musician. All I had to do was to listen inside me. The music started to flow easily...

BS: Another highlight that same year came with The Hindenburg. Here you had the chance of working with one of the greatest filmmakers ever, Mr. Robert Wise, who sadly passed away recently. How did you approach this project?

DS: It was a matter of chance. I worked for Universal, and someone from Universal talked to Robert Wise about my music, so I had an interview with the director, and I was really impressed by his talent. He was already a legend in Hollywood, very smart; he appreciated my music very much, so I was pleased and very comfortable to work by his side.

BS: It is surprising how easy you seem to move from very large studio-typed films to rather small projects. What are the tricks of your trade with film industry?

DS: There are no tricks. You simply end by scoring what is put in front of you. The size of the film matters more than the size of the screen or the budget you are in. I am a professional score writer, so I score what I’m asked to score. I don’t think there’s any trick in order to take one direction or another. Each composer, at least, has his method.

BS:  Saturday Night Fever is quite famous for the cult songs created by the Bee Gees. However, the additional music you wrote, and in particular the theme "Manhattan Skyline", became also very familiar to the general public. Are you proud of having taken part in such a legendary title? Saturday Night Fever is quite famous for the cult songs created by the Bee Gees. However, the additional music you wrote, and in particular the theme "Manhattan Skyline", became also very familiar to the general public. Are you proud of having taken part in such a legendary title?

DS: It is always wonderful to take part in a film that’s making history. But I can tell you that at the time the film was being shot and produced no one had any idea of the social impact it was going to have. I am certainly proud of my small contribution to that hit movie. Director John Badham and all the crew had lots of fun in the making of it, regardless of its transcendence.

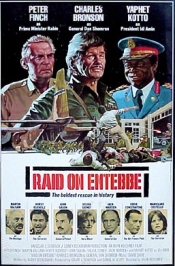

BS: In 1977 you wrote the music for an Irvin Kershner’s TV production: Raid on Entebbe. The main theme is incredibly dynamic, making a noteworthy use of the piano as a percussion instrument. Film music fans are always surprised by the quality of this score, given the fact that it was not written for the big screen...

DS: You should take into account that TV movies can sometimes count on a million dollar budget. I was fortunate to work in that project, with an 80 piece orchestra and all the facilities I asked. I was given four pianos to work with, so I took advantage of the situation. If I had to work with a smaller budget, I would have thought another score...

BS: You won in fact an Emmy Award nomination for this score. Did you expect this to happen?

DS: I never expect a prize. It’s great to have a nomination because this means that your music is appreciated in terms of art contribution, but prizes are always a surprise, something you should not expect to happen.

BS: Is film scoring a more difficult task than song-making?

DS: In my own approach to music writing I always tend to be melodic. When I work for the theatre plays I prefer the singing lines, but they cannot be very much adequate for some films, and my responsibility as a composer is to give to each scene an adequate music. I’m, in other words, more comfortable when I write songs, but I try to do also a good job with instrumental music.

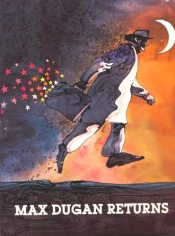

BS:  In 1983, your score for Max Dugan Returns ranked again among the best pieces of music you have ever written. It has a very vigorous main theme... In 1983, your score for Max Dugan Returns ranked again among the best pieces of music you have ever written. It has a very vigorous main theme...

DS: I was doing dance music at that time, so I planned it somehow as a choreography job... Director Herbert Ross came to meet me and said he was rather disappointed with my score, so I remember I had to go back home and start another score... I think now that Ross was right, the second score fit better than the previous.

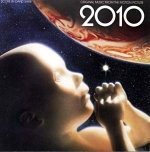

BS: In 1984, you were asked to write the music for the sequel of a filmed masterpiece: 2001. Director Peter Hyams decided to bring back Arthur Clarke’s novel to the big screen with 2010. How did you manage to score this picture?

DS: I interviewed Peter Hyams with no particular reason and we decided to work in such a project. In fact, 2001 had a soundtrack based on classical music, with a magnificent result. However, Hyams wanted a different approach, and he asked me to write new music for the mythical film sequel. I used electronic music in this particular case in order to seem more futuristic.

BS: More sci-fi projects: In 1985 you scored some episodes of the cult series Amazing Stories, produced by Steven Spielberg. Can you provide us some insight into this project?

DS: I just wrote two or three episodes. I remember what I had in mind those days: a possible chance to work with Spielberg in any other project... I admire him most, but that was just a dream; it just never happened... Why? Because Steven Spielberg can count on the best film music writer available: John Williams. Whatever Spielberg has in mind, Williams will compose the best score for his idea. He’s a genius, and very versatile... In fact, if I were in Steven Spielberg’s place I would also ask John Williams to write music for my films.

BS:  Return to Oz is likely to be among the most praised scores by film music fans. It is often put as an example of a thematically and stylistically varied and rich score. Does this music have a particular meaning to you? Return to Oz is likely to be among the most praised scores by film music fans. It is often put as an example of a thematically and stylistically varied and rich score. Does this music have a particular meaning to you?

DS: This was one of the most satisfying experiences in my life. It involved a long creative period, of about 6 months, in which I was offered to conduct the London Symphony Orchestra. I also met an amazing sound editor, Walter Murch, from whom I learnt a lot. I’m happy that fans can recognize all the art put in that score, despite the fact that the picture didn’t work well in terms of popularity. I had really a good time when scoring Return to Oz.

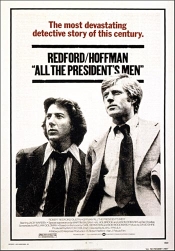

BS: This kind of music seems very opposite to some of your earlier low key works: The Conversation or All the President's Men. Would you now like to score more movies like Return to Oz?

DS: Of course I would! Unfortunately those kinds of projects never reached my hands because there was always someone right above me... Authors like Williams or Goldsmith were clear first step composers for almost every director or producer for a big film. I particularly admire Williams’ capacity to write a perfect score for each project in which he is being involved, no matter how difficult, how subtle or how strange. After many years, he is still disputing music scores to many young and talented composers of two forthcoming generations... I feel it’s not my day anymore. Now I live in New York, and I’m happy writing music for Broadway shows.

BS: Coming back to All the President's Men, it is striking how small it is the amount of music you composed, given the total length of the film.

DS: I definitely wrote many more music which wasn’t used. Director Alan Pakula wasn’t sure from the start on how much music the film was going to need. He wanted it to be almost like a documentary, so he finally used only 20 minutes of music (and I wrote more than 40).

BS: One of the main shortcomings any film music fan may have has to deal with trying to get more acquainted with your work by buying the official soundtrack releases. Often these are no longer available in stores or, alternatively, quickly sold out because they have been released in a very limited edition. Is there a score in particular that you'd like to see released for the first time or re-issued more widely?

DS: Not one but ten or twenty instead... Recently someone asked me to work on a re-issue for Max Dugan Returns... Now I don’t feel very comfortable to go back to the studios and do more recording sessions, but I must admit that there are some there some themes that could match a nice CD.

BS: Did you know that the official Bay Cities edition to Return to Oz is from time to time being auctioned in eBay at an exorbitant price?

DS: What’s an exorbitant price?

BS: More than one hundred dollars.

DS: Really? Then I should treasure the copies I keep with such care, for the value they may acquire in the future...

BS: One of the distinctive features of your writings is the deliberate effort to come up with themes that play strongly on the subtext of the story, instead of simply retelling what’s on the screen. Is this something you are conscious about? Do you work very close to each director?

DS:  As I told before, writing music for the big screen brought me the opportunity to merge with other crew members, creative artists who were involved in the film the same as I. I’ve had very good conversations with directors, to my pleasure and also for the benefit of the film’s music. Sometimes you need some ideas coming from the director about the music you are to write; on the contrary, sometimes is the director who comes to you with a scene that’s not enough complete and needs some music reinforcement... It is a splendid relationship, and I’ve been very lucky to discuss film art through long conversations with many talented directors such as Francis Ford Coppola, John Badham, Alan Pakula and others. As I told before, writing music for the big screen brought me the opportunity to merge with other crew members, creative artists who were involved in the film the same as I. I’ve had very good conversations with directors, to my pleasure and also for the benefit of the film’s music. Sometimes you need some ideas coming from the director about the music you are to write; on the contrary, sometimes is the director who comes to you with a scene that’s not enough complete and needs some music reinforcement... It is a splendid relationship, and I’ve been very lucky to discuss film art through long conversations with many talented directors such as Francis Ford Coppola, John Badham, Alan Pakula and others.

BS: Having worked for theatre plays, TV series or big screen films, there must be any filed you prefer the most?

DS: I’m a professional musician, and I feel equally comfortable with the three. The good thing is that you can learn things in one field that can apply then to another. I wonder if a camera man or a customs designer can share such a rich opportunity.

BS: Short Circuit meant an additional collaboration with director John Badham. It also made you the winner of a BMI Film Music Award. What do you remember about this score?

DS: I have worked repeatedly with John Badham. He’s an old friend of mine since the days when we were studying at Yale University. In this particular project John asked me to compose a very futuristic theme to be appropriate enough for a robot. I mixed then some electronics with a typical orchestra arrangement. DS: I have worked repeatedly with John Badham. He’s an old friend of mine since the days when we were studying at Yale University. In this particular project John asked me to compose a very futuristic theme to be appropriate enough for a robot. I mixed then some electronics with a typical orchestra arrangement.

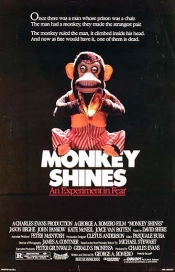

BS: In 1988 came the film Monkey Shines... How was it like to work for director George Romero?

DS: George Romero thought of a movie which meant a lot of fun to me. One think is to score a monkey, and a different think is to score an evil monkey... The more elements that are combined in a single subject, the more I enjoy writing music about. Circus music, jungle percussions, different music approaches melt in one particular theme.

BS: One singularity about this score is the strong contrast between the melodic passages of your music and the dark atmosphere conveyed by what we see on the screen. Was this a conscious decision you made?

DS: The movie intended to bring a mad impression, so I just did my job. I want to stress the fact that I enjoy very much the complex characters in a film. They give me an opportunity to display my musical creative imagination better than a simple definition.

BS: You were again nominated for an Emmy Award in 1990, for your work in the mini-series The Kennedys of Massachusetts. What can you tell us about this score?

DS: The series required a lot of music, so I had a lot to write. I was given a good budget, a very good orchestra, and I also used many Irish themes in the music.

BS:  Two years later you wrote a score for Bed & Breakfast, starring Roger Moore. The score includes a delightful violin solo theme... Two years later you wrote a score for Bed & Breakfast, starring Roger Moore. The score includes a delightful violin solo theme...

DS:-There is a funny anecdote about that project. I was very nervous to know who would be the violinist for such a difficult task. I was given to conduct the Irish Film Orchestra, and was told to rely on the concertmaster... I insisted to know who would be this person, because there was no concertmaster in the first recording sessions. So a huge strong lady then came to me and said she would do the violin solos... I was greatly disappointed to see that big woman trying to perform a very delicate violin solo. Her fingers just didn’t fit with my idea of a talented violin player. She excused herself for having not attended the sessions but insisted on the solos... I was afraid to say no, because she was so strong that she could easily broke my bones in case of anger... But she performed very gently and I realized she was indeed a very talented violinist.

BS: Are you happy with the soundtrack released by Varese? It is nowadays virtually impossible to find it anywhere...

DS: I’m very happy. I think it made a beautiful record: It is certainly a shame that’s so difficult to find, even for me... I had to copy it down to my computer in order to have any more copies available DS: I’m very happy. I think it made a beautiful record: It is certainly a shame that’s so difficult to find, even for me... I had to copy it down to my computer in order to have any more copies available

BS: Then came a western for TV: Last Stand at Saber River, starring Tom Sellek (1997) Why didn’t you write more western type soundtracks?

DS: I don’t know. To be true, there haven’t been many western movies shot in recent years. However, I feel very comfortable writing western music. It was in my origin as a composer, with The Virginian, and I have always loved to score far-west movies.

BS: After such a long and memorable career in film music, what does still motivate you to keep on composing?

DS: I insist that I’m a professional composer. It’s all about getting a job. I have witnessed at least three generations of film composers. First came the Williams and Goldsmiths, then the Horners and Zimmers, now with so many talented musicians who try to adequate a piece of music to a particular scene... Maybe I’m now more comfortable working for Broadway shows, but my motivation is always music, nothing more, nothing less. nothing more, nothing less.

BS: How do you feel with the edition of records such as “David Shire at the Movies” and “David Shire Film Music”?

DS: I enjoyed seeing all this projects of mine being put all together. I guess it would cost a fortune to put all my music in a commercial effort... So I enjoy with these particular works. I admit that some pieces sound strange, because they are played by a chamber orchestra and were initially written for a full symphonic orchestra, but the final cut is fairly acceptable.

BS: Now, let’s talk about your career in scoring Broadway musical shows. How did it all start?

DS: As you know, musicals have been always an important part of my life. Since I took up the piano as a child I felt very much interested in show-business. I played in my own father's dance band at local functions in and around Buffalo, and majored at music at Yale University. It was there that I met lyricist Richard Maltby Jr. We both headed for New York, where we started working together on quite a few off-Broadway musicals such as Sap of Life (1961) and Love Match (1968). Although I started scoring TV series and films later on, I never quit the theatrical shows... In fact, I’m currently working on three of them. My wife, Didi Conn, is also producing a new TV animated series for children. Each episode is presented as a miniature musical show, and I’ve been asked to write the music. I’ve written a lot of music for plays and songs for cabaret shows through all my life. Some have succeeded, others haven’t. In Broadway, you never know...

BS: So you probably paid more attention to show song-writing that to film scoring...

DS: Theater music plays perhaps a bigger role in my career as a composer, but I couldn’t choose one source of creativity without the other... Is like having to choose who your favorite child among your children is. The shows tend to demand a more background oriented work, while the films are more foreground. You end writing music in both, but I think they are two different jobs.

BS: In 1967 you worked in The Unknown Soldier and His Wife. How did you get involved in it? What can you tell us about this work?

DS: This is a nice remembrance... I was recommended by Stephen Sondheim to Peter Ustinov as a sort of "young promising musician". So Peter and I work together on that play, and I took that job with a lot of responsibility. DS: This is a nice remembrance... I was recommended by Stephen Sondheim to Peter Ustinov as a sort of "young promising musician". So Peter and I work together on that play, and I took that job with a lot of responsibility.

BS: In 1984 you wrote Baby. Where did you take the idea?

DS: There is a touching anecdote about that play. At that time, my brother-in-law Francis Ford Coppola was also interested on Broadway shows and theater, so we had a long talk driving through the alleys and I asked Francis what direction did he think that plays should take, what could be the future of theater. "I think of small plays, low budget productions about personal and real emotions, real stories with real people..." I told him I was about to write something like that. "Could you figure any topic?", I asked. "Think about the most meaningful fact in your life, and write a play about it." The most meaningful fact was indeed my son Matthew’s birth, so I decided to write not about having a child, but about those nine months prior to birth, mixing different attitudes towards this unique experience of expecting a child.

BS: Then you got a Tony nomination in Best Original Score category and a Drama Desk nomination in Outstanding Music category. Did you expect this to happen?

DS:Baby had also a nomination for best musical... We were very delighted with such recognition. We knew it was hard to win, because Stephen Sondheim was leading all the best critics, but it was nice to be invited to the gala party. We had a good time.

BS: Were those awards a key impulse to your career in Broadway?

DS: Yes, but the business deeply changed during the late 80s and the 90s, so Francis was right. Small shows began to replace the big shows, and companies like International Music Theater started to deliver shows all over the world with a great success. Some weren’t really a hit in Broadway, but were very well credited in other cities. DS: Yes, but the business deeply changed during the late 80s and the 90s, so Francis was right. Small shows began to replace the big shows, and companies like International Music Theater started to deliver shows all over the world with a great success. Some weren’t really a hit in Broadway, but were very well credited in other cities.

BS: But recognition didn’t stop: you soon obtained another Drama Desk nomination with Closer than Ever in Outstanding Music category...

DS: A young director asked me to write only six songs to be put together with other songs he had previously chosen, but the play received very great reviews from The New York Times, so I was asked to write more music... Closer than Ever clearly succeeded during a whole year at the Cherry Lane Theater in Greenwich Village, and a double-CD edition of the music was then edited as well.

BS: Then you wrote the music for Big, a play inspired in that film starring Tom Hanks. How much different were both the film and the play soundtracks?

DS: Music tries to reflect that same emotion in both cases. The movie focuses in Josh and Susan’s experience, while the play goes more inside each single character. To me, a musician has the same challenge in the play or in the film, but he will have to deal with different problems.

BS: Is Big the most satisfying musical you have ever written?

DS: To be honest, I think that Baby is my best complete show, and very personal. However, now I’m facing with very much enthusiasm my next show, Take Flight, which I expect to be very moving and successful. I’m presently working on the orchestrations.

BS: What is your favorite Big song in the CD:"I want to Go Home", "This Isn't Me", "Talk to Her / Carnival / Zoltar Speaks"...?

DS: I’m afraid the recording was not very good, and many good songs weren’t included. So the CD might be not a representation of what the play was about.

BS: Tell us about you collaboration with Richard Maltby in Cyrano and other plays...

DS: We both have worked with several people, but we both agree that our best of times has been working together. Our songs have been sung by very well-known artists like Barbra Streisand, Maureen McGovern, Melissa Manchester, Jennifer Warnes, Kiri Te Kanawa and Billy Preston. Nevertheless, Richard has also worked in big standard plays such as Miss Saigon or Ring of Fire, based in Johnny Cash’s story.

BS:  Are Broadway shows and cabaret shows different from the composer’s perspective? Are Broadway shows and cabaret shows different from the composer’s perspective?

DS: Yes, Broadway shows always follow a plot, a book, while in cabaret you have more freedom to communicate with the listening audience. I both find pleasure in writing a piece for a cabaret or a Broadway show.

BS: What was your first experience in cabaret song writing? How did you begin in Cabaret’s world? What was your first experience in cabaret song writing? How did you begin in Cabaret’s world?

DS: "Starting here, starting now".

BS: You took part in the Adelaide Cabaret Festival. Please, tell us about that experience.

DS: We did a concert with some Take Flight songs, performed by Australian artists. It was a great experience and a true success.

BS: That’s all Mr. Shire. Thank you very much for your gentleness.

DS: You are always welcome.

Interview made by Jose Luis Díez Chellini

Transcription by Jordi Montaner and Óscar Giménez

Questions by David Doncel, Sergio Gorjón y Asier G. Senarriaga

|